Early Christianity Articles

To us in the 21st century, the first Council of Nicaea is like a mountain in the landscape of the early church. For the protagonists themselves, though, it was more of an emergency meeting forced on the parties by the Roman imperial power to stop an internal religious squabble.

The bishops found themselves in a swamp of controversy that, at times, seemed to threaten the very life of the early Christian church.

To understand the council's significance, we need to enter the minds of the two sides of the dispute and ask why the question of Jesus' divinity caused so much bitterness and confusion. The answer: like other "simple" questions, this was in fact a highly complex and provocative theological issue.

Who came to the gathering of bishops? Of the roughly three hundred clerics, most were from Eastern churches, with only six or seven recorded as having come from Western. Among them were Ossius of Cordoba, Caecilianus of Carthage, and two representatives from the church of Rome. "The small number from the West reflected the general ignorance among churches of those theological issues that had embroiled the East," according to D.H. Williams, professor of patristics and historical theology.

Archbishop Alexander

The argument began with Archbishop Alexander in Egypt. He was a follower of Origen, who had explored the mystical relationship of the divine Logos to the eternal Father. The word Logos came from the Greek Bible and meant "Divine Wisdom."

To many Christians, it seemed a wonderful way to talk about the eternal Son of God and became almost a synonym for the Son. Alexander said the Logos shared the divine attributes of the Father . . . "born of God before the ages." Since God the Father used the Logos as the agent of all creation, it followed that the Son pre-existed creation.

Presbyter Arius

One of Alexander's senior priests, the presbyter Arius, was scandalized by his theological position on this issue. Arius, who had charge of the large parish of Baucalis, had also been an intellectual disciple of Origen. The Son, Arius allowed, might well have pre-dated the rest of creation, but it was not wise to imagine that he shared the same divine pre-existence.

Thus, it was important to confess the principle that "there was a time when he (the Logos) was not." Arius put this axiom into a rhyme and taught it to his parishioners, who soon chanted the slogan to all who would listen.

"Foolish Piety"

Alexander would not allow a theologian's dispute to mushroom publicly in this alarming way. And so he censured Arius for appearing to deny the Son's eternity and true divinity. Arius appealed the decision to a powerful bishop of the era, Eusebius of Nicomedia--a relative to Constantine the emperor. Arius and Eusebius shared similar theological views.

Eusebius, a member of the imperial court, knew if Arius was being attacked then so was he. From that moment onwards, he was determined to squash what he regarded as "foolish Egyptian piety."

Nicaea Council

The split between the two factions was so serious that the matter was brought to Constantine's attention. He decided to use the occasion of his 20th anniversary as emperor of the Roman Empire to settle the issue. Constantine summoned the bishops to his private lakeside palace at Nicaea, paying all their expenses. The council opened on June 19 in AD 325. Tradition says that 318 clergies were in attendance.

A few bishops were determined to lobby for the Alexander view. They wanted to refine the baptismal creed of Jerusalem, submitted by Eusebius of Caesarea as a blueprint for a "traditional statement of faith." They believed this statement of faith was authentic, but it didn't really resolve the precise issue under debate. So they decided to amend it with additional wording about Christ.

The Magic Word

The origin of these "confessional acclamations" of Christ ("God from God, Light from Light" etc.) was Alexander's party, but many of these bishops demanded a firmer test of faith. It is said that Ossius, the theological advisor to the emperor, suggested that the magic word to nail the Arian party would be homoousios.

The term meant "of the same substance as," and when applied to the Logos it proclaimed the Son was divine in the same way as God the Father. In short, if the Logos was homoousios with the Father, he was truly God alongside the Father. The word pleased Constantine, who seems to have seen it as an ideal way to bring all the bishops back on board for a common vote.

But for the Arian party, the word went too far. It gave the Son equality with the Father without explaining how this relationship worked. It undermined the biblical sense of the Son's obedient mission. Eusebius of Nicomedia and others said the word attributed "substance" (or material stuff) to God, who was beyond all material. It also was "not found in the Holy Scriptures."

The great majority of the bishops still endorsed the idea, however; and with Constantine pressing for a consensus vote, the word entered into the creed they published. In the end, the bishops meeting at Nicaea proclaimed an ancient Christian creed of faith, with a common and clear heritage that began when the Holy Spirit led all of Christ's apostles to the realization of the gospel truth.

(Source: Christian History & Biography, by John Anthony McGluckin, professor of early church history at Union Theological Seminary and professor of Byzantine Christianity at Columbia University in New York.)

Constantine and the Bishops

In the year AD 324, the Roman emperor Constantine the Great dispatched his closest advisor, Ossius of Cordoba, to mediate the dispute between the Empire's bishops within the Christian church over the divine nature of Jesus the Christ.

Ossius carried a letter that set out the emperor's thoughts in all their simplicity. The letter has been preserved and reads:

Victor Constantius Maximus Augustus to Alexander and Arius

I call upon God himself to witness, as I should, the helper in my undertakings and Saviour of the Universe that a two-fold purpose impelled me to undertake the duty, which I have performed. My first concern was that the attitude towards the Divinity of all the provinces should be united in one consistent view, and my second that I might restore and heal the body of the republic, which lay severely wounded. In making provision for these objects, I began to think out the former with the hidden eye of reason, and I tried to rectify the latter by the power of the military arm. I knew that if I were to establish a general concord among the servants of God in accordance with my prayers, the course of public affairs would also enjoy the change consonant with the pious desires of all.

In Constantine's opinion, the dispute was indeed grievous, but "the cause was . . . trivial and quite unworthy of such controversy." Those on both sides of the argument surely felt otherwise, since for them the nature of Christ affected the salvation of all for whom he died.

To those opposed to Arius, he was a heretic who claimed that the Son was less than fully God, denied the divinity of his sacrifice, and hence barred the possibility of theosis, the deification of mankind.

To Arius, those who maintained that the Father and the Son were equally eternal and of the same substance were misleading their congregations into an earlier heresy (Sabellianism), which treated the Godhead as unitary, and the Son and Holy Spirit as aspects of divinity.

Orthodoxy and the issue of salvation were not, to either party, trivial matters. Therefore, neither was likely to favor Constantine's offer to act as a "peaceful arbitrator between you in your dispute."

When Ossius achieved no consensus from the two sides, he offered to preside at a council in Antioch, where the recent death of the bishop there had led to the disputed election of a certain Eustathius, who was then confirmed by Ossius.

But the Arians preferred another man, the bishop of Caesarea, whom we know as Eusebius, Constantine's biographer. The Antioch council excommunicated Eusebius and two other bishops, but also invited them to a further council in Ancyra (modern Ankara), to confirm their acceptance of the majority view.

But this decision didn't please Constantine, who had witnessed problems when only bishops ran a council meeting. He was determined they must come to him, and so he sent a letter summoning the clerics to Nicaea in the region of Bithynia.

He selected Nicaea because the bishops from Italy (except the one from Rome) and the rest of the countries of Europe were coming, and because of the excellent weather and "in order that I may be present as a spectator and participant in those things that will be done."

The only eyewitness account of the Council of Nicaea, which was only later called the first ecumenical council of the church, was written by Eusebius of Caesarea about a decade afterward.

It was at the council that Eusebius met Constantine for the first time. He was evidently impressed by the pomp and ceremony that surrounded the imperial leader. Eusebius elected to describe the emperor's demeanor and majesty in handling the querulous bishops rather than the deliberations of the synod. This was correct given the nature of his work.

His account became the basis for all later descriptions of the Nicaea synod, and consequently for the magnified role that Constantine played. We can say little more than Constantine gave a speech of welcome in Latin to the more than 250 bishops--later tradition holds there were 318, corresponding to the number of Abraham's servants in Genesis 14--mostly Greek-speakers, who attended at his expense, and that he acted on occasion as a mediator in the controversy. It seems certain, however, that Ossius of Cordoba played the role of the unmentioned underling who took charge--in this case chairing sessions and controlling theological disputes.

It would be later charged that Constantine, or Ossius, shut down all intellectual exchange, imposing instead a solution based on the use of the term 'consubstantial (homoousios). By using the very word that Arius rejected as the root of the heresy of Sabellianism, the fate of the preacher was sealed. Arius was condemned and exiled with two bishops who refused him to agree to the statement of faith, which came to be known as the Nicene Creed.

Another bishop named Eusebius--this one from Nicomedia--also signed the creed but didn't agree to the exile of Arius. He was then charged with corresponding with Arius and also exiled by order of the emperor. This was a striking turn of events, for Nicomedia was still Constantine's imperial capital.

The method for determining the date for Easter, which all must observe, was also agreed upon, and Constantine undertook to enforce universal observance or orthodoxy.

The end of the council coincided with the end of Constantine's vicennial, and so the bishops were invited to the imperial palace in nearby Nicomedia--in AD 325 Constantinople was not yet complete--to dine and celebrate the emperor's twentieth year in power. Constantine then sent the bishops away with gifts and large cash donations for their churches.

(Source: Constantine: Roman Emperor, Christian Victor, by Paul Stephenson, 2009)

Persecution of Early Christians

Today's growing hostility toward Christianity spans many centuries, beginning of course with Christ himself when he was crucified. His followers, in turn, have been persecuted and even put to death for their beliefs.

Two books by Bible scholar and historian Larry Hurtado explain why early Christians were persecuted more than any other religious group in the first three centuries.

Hurtado was an Emeritus Professor of New Testament Language, Literature, and Theology at the University of Edinburgh, in Scotland.

The following is a reprint of an article of Hurtado's views about the early church. The author is Timothy Keller of Redeemer Presbyterian Church. The article appeared in Redeemer Report (November 2016).

____________________

"These volumes explain that the early Christians were persecuted more than any other religious group in the first three centuries because they refused to honor other gods or worship the emperor and therefore they were seen as too exclusive, too narrow, and a threat to the social order.

Hurtado asks the obvious question that a historian should ask. Why, if Christians were seen as so narrow and offensive and were excluded from circles of influence and business and often put to death — why did anyone become a Christian?

One of the main reasons was that the Christian church was what Hurtado calls a unique 'social project.'

They were a contrast community, a counter-culture that was both offensive and yet attractive to many. We mentioned this briefly in November, but here we will spell out what made the Christian community so different.

Hurtado points out that the basis for this unusual social project was the unique, new religious identity that Christians had. Before Christianity, there was no distinct “religious identity” because one’s religion was simply an aspect of one’s ethnic or national identity.

If you were from this city, or from this tribe, or from this nation, you worshipped the gods of that city, tribe, or people. Your religion was basically assigned to you.

Christianity brought into human thought for the first time the concept that you chose your religion regardless of your race and class. Also, Christianity radically asserted that your faith in Christ became your new, deepest identity, while at the same time not effacing or wiping out your race, class, and gender. Instead, your relationship to Christ demoted them to second place.

That meant that, to the shock of Roman society, all Christians, whether slave, free, or high born, or whatever their race and nationality, were now equal in Christ (Galatians 3:26-29). This was a radical challenge to the entrenched social structure and divisions of Roman society, and from it flowed several unique features.

(1) The early church was multi-racial and experienced a unity across ethnic boundaries that was startling. See the description of the leadership of the Antioch church in Acts 13 as just one example.

Throughout the book of Acts, we see a remarkable unity between people of different races. Ephesians 2 is testimony to the importance of racial reconciliation as a fruit of the gospel in the lives of Christians.

(2) The early church was a community of forgiveness and reconciliation. As we have said, Christians were often excluded and criticized but also they were actively persecuted, imprisoned, attacked, and killed.

But Christians taught forgiveness and withheld retaliation against opponents. In a shame and honor culture in which vengeance was expected, this was unheard of. Christians never ridiculed or taunted opponents, let alone repaid them with violence.

(3) The early church was famous for its hospitality to the poor and the suffering. While it was expected to care for the poor of one’s family or tribe, Christians’ ‘promiscuous’ help given to all poor, even of other races and religions, as taught in Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10: 25-37) was unprecedented. (See Gary Ferngen, “The Incarnation and Early Christian Philanthropy” online.)

During the urban plagues, Christians characteristically did not flee the cities but stayed and cared for the sick and dying of all groups, often at the cost of their lives.

(4) It was a community committed to the sanctity of life. It was not simply that Christians opposed abortion. Abortion was dangerous and relatively rare. A more common practice was called “infant exposure.”

Unwanted infants were literally thrown out onto garbage heaps either to die or to be taken by traders into slavery and prostitution. Christians saved the infants and took them in.

(5) Finally, it was a sexual counter-culture. Roman culture insisted that married women of social status abstain from any sex outside of marriage, but it was expected that men (even married men) would have sex with people lower on the status ladder — slaves, prostitutes, and children.

This was not only allowed but was regarded as unavoidable. This was in part because sex in that culture was always considered an expression of one’s social status. Sex was mainly seen as a mere physical appetite that was irresistible.

Christians’ sexual norms were different, of course. The church forbade any sex outside of heterosexual marriage. But the reason the older, seemingly more ‘liberated’ pagan sexual practices eventually gave way to stricter Christian norms was that the “deeper logic” of Christian sexuality was so different.

It saw sex as not just an appetite but as a way to give oneself wholly to another and in doing so imitate and connect to the God who gave himself in Christ.

It also was more egalitarian, treating all people as equal and rejecting the double standards of gender and social status. Finally, Christianity saw sexual self-control as an exercise of human freedom, a testimony that we are not merely the pawns of our desires or fate. (See Kyle Harper, From Shame to Sin: The Christian Transformation of Sexual Morality in Late Antiquity, Harvard University Press, 2013).

It was because the early church did not fit in with its surrounding culture, but rather challenged it in love, that Christianity eventually had such an impact on it. Is it possible that essentially the same social project could have a similar effect if it was carried out today?"

How We Got the Bible

We find it almost impossible to think of the Christian faith without the Bible. It's the foundation of evangelism, teaching, worship, and morality. Looking back over Christian history, we find few decisions more basic than those made during the first three centuries surrounding the Bible's formation.

The Scriptures served not only as the inspiration for believers facing martyrdom but also as the supreme standard for the churches threatened by heresy. If catholic (universal) Christianity was orthodox, the Bible made it so, for the constant test of any teaching was, what do the Scriptures say?

We need to ask, then, how did we get the Bible?

The word Bible suggests that Christians consider these writings special. Jerome, the fourth-century translator, called them "the Divine Library." He stressed that its many books were, in fact, one book. Greek-speaking believers made the same point, calling it "The Book."

The Jews had faced the same problem when they spoke of The Scriptures and Scripture. That explains how the Bible and Scripture came to mean the same thing in Christian circles: the sixty-six books that followers of Christ consider the inspired, written word of God.

Today, we find the Scriptures grouped under Old Testament and New Testament. In the ancient world a "testament," or more often a "covenant," was the term for a special relationship between two parties. We still speak of the "marriage covenant" between a husband and wife.

Used in the Bible, the term stands for the special relationship between God and man, sustained by the grace of God. The old covenant was first between the Lord and Abraham, then between God and Abraham's descendants, the children of Israel. Later years knew them as Jews, whose ancient worship of God is told in the Old Testament.

Early Christians believed that Jesus of Nazareth was God’s promised Messiah, who established a new covenant with his new people, the church. So the New Testament contains the books that tell the story of Jesus Christ and the birth of the church.

In short, then, the Old Testament promised and the New Testament fulfilled.

The word for the special place these books occupy in Christianity is canon. The term from the Greek language originally meant “a measuring rod” or, as we might say, “a ruler.” It was a standard for judging something straight. The idea transferred to a list of books that constituted the standard or “rule” of the churches. These were the books read publicly in the congregations because they had God’s special authority upon them.

Since the first Christians were all Jews, Christianity was never without a canon or scripture. Jesus himself clearly accepted the Old Testament as God’s word to man. “Scripture cannot be broken,” He said. “Everything written about me in the law of Moses and the prophets and the psalms must be fulfilled,” (John 10:35; Luke 24:44).

Jesus believed the statements of Scripture, endorsed its teaching, obeyed its commands, and set himself to fulfill the pattern of redemption it laid down. Early Christians were heirs of this attitude. Had not the hopes and plans of the old covenant come true in Jesus? Had not the promised messianic age dawned in him?

Early believers went to exaggerated lengths to make the Old Testament into a Christian book. Their interpretations of Scripture often kept to the historical pattern of promise and fulfillment used by the New Testament writers.

But some resourceful writers went far beyond this basic theme. They soon developed a method of interpretation that discovered Jesus Christ and the Christian message all through the Old Testament. We call this allegorical interpretation, because it turns seemingly actual events, such as the crossing of the Jordan River, into a symbol of baptism or some other Christian truth.

By the third century, the church had scholars who could defend Christian claims to the Old Testament by the use of allegory. The most influential was a teacher at Alexandria, Egypt, named Origen, who spoke of the different levels of Scripture:

“The Scriptures were composed through the Spirit of God, and have both a meaning which is obvious, and another which is hidden from most readers . . . . The whole law is spiritual, but the inspired meaning is not recognized by all—only by those who are gifted with the grace of the Holy Spirit in the word of wisdom and knowledge.”

Christian appeals to allegory infuriated pagan critics of the faith because they took the Old Testament at face value. The move remained popular, however, since it enabled Origen and other believers to find the Christian message just beneath the surface of the Old Testament.

The second article in this series will take up the question of the so-called Apocrypha list of books in the Old Testament that Roman Catholics accept as canonical and most Protestants reject.

(Source: Church History in Plain Language by Bruce Shelley, 1995)

Marriage in Byzantium

The Council of Nicaea is often misrepresented. Modern critics of the divinity of Christ allege that the council was a tool of imperial manipulation.

They point to Nicaea, not the Bible, as the source of the doctrine of the Trinity, and interpret the Council as the triumph of heresy over orthodoxy, rather than the reverse. They argue that Emperor Constantine "forced" the Council to adopt the crucial word 'homoousios' to describe the equal divinity of the Father and the Son.

But did Constantine really run the show at Nicaea?

The relationship between the church and the emperors starting with Constantine to the end of the Roman Empire in the East (also known as the Byzantine Empire, AD 330-1453) worked much like a marriage.

Much of the relationship was improvised, and the lovers quarreled at times and manipulated each other to get what they wanted. When it came to matters of faith, however, the boundaries of their association were clear about where the power of one left off the other began.

Defender of the faith

In 336, the 30th year of Constantine's reign, Eusebius of Caesarea gave a speech in honor of the emperor. His talk was an official statement of the imperial image and political theory that would define the role of the emperor until the fall of the Byzantine Empire.

Eusebius affirmed Constantine as God's anointed one, an earthy reflection of the image of Christ in heaven--one God, one emperor, one kingdom, and one faith. Eusebius did not believe Constantine was divine, but he did see him as God's representative over the Christian empire.

The emperor was also the divinely appointed defender of the faith, the "pontifex maximus"--a Christianized pagan title for the supreme leader of a religion that made the church a department of the state.

What happened at Nicaea is true of all the ecumenical councils (AD 325-787) as they confessed the Trinity, the divine and human natures of Christ, and the justification of icons in worship and devotion.

Four points summarize the relationship between church and emperor at all the ecumenical councils.

Who's in charge here?

First, the ecumenical councils were imperial councils.

Emperors convened them, and their proceedings were patterned after those of the Roman Senate. The emperors also confirmed the election of bishops, convened or prevented church councils, and presided over them to some extent.

At the Council of Nicaea, Constantine "pushed" the bishops to adopt the crucial term homoousios that was likely suggested to him by his theological advisor, Bishop Ossius of Cordoba.

Constantine was not a theologian--in fact, at the time, he was technically not even a Christian. His main goal of imperial unity, not theological accuracy.

Innovation is not a virtue

Second, the ecumenical councils were conservative.

Doctrinal innovation was not a virtue in the minds of the emperors or early church fathers. Their task was not to invent doctrine but to confess it.

In so doing, they appealed to "following the Holy Fathers" so that what had been believed would also be passed on. Hence, the very words, phrases, and sentences of the "holy and God-bearing Fathers" were collected and cited in documents of the period.

Third, the councils functioned as witnesses to the truth.

The councils were intended to be an expression of the church, not a forum to clarify differences. Their purpose was to take the consensus of what the bishops believed, not to determine truth through argument.

The imperial council could not be a place to debate heretics who, by definition, could not participate since they were in principle not members of the church.

The problem, of course, was to decide ahead of time who was a heretic, and that was seldom clear at the time. The emperors were only too eager to help clarify that assurance issue.

Fourth, the ecumenical councils were viewed as Spirit-inspired events.

The councils were not legal institutions that guaranteed the truthfulness of their decisions. This view limited imperial power. Constantine and his successors learned from the church's response there was no assurance a council's decisions would be adopted by the universal church.

Under the Holy Spirit's guidance, Nicaea was a witness to the truth, conforming with Scripture as handed down in apostolic tradition. However, its authority would be determined only if the church received it.

The ultimate authority of the ecumenical councils was not the emperor, but the witness of the Holy Spirit among the faithful and their bishops.

(Source: Christian History & Biography, by Bradley Nassif, professor of biblical and theological studies, North Park University, Chicago.)

Athanasius: Defender of Orthodoxy

A modern biographer of Athanasius of Alexandria speaks of "the predominantly polemical nature of most of his works" and "the lack of serenity in his argumentations."

In all of Christian history, it is safe to say, few churchmen have been so entirely embroiled in doctrinal and ecclesiastical disputes as Athanasius. In comparison with him, even so, controversial a figure as Martin Luther lived out a relatively quiet and uneventful life.

Born into a Christian family in Alexandria in AD 295, Athanasius was an infant during the persecution by Diocletian and barely more than a boy when the Edit of Milan legalized the church in 313. He was ordained a deacon five years later at age 23, and his entire life was absorbed in the service of the church.

The event that most marked the destiny of this ardent churchman was the Council of Nicaea. There is perhaps no other name more closely identified with Nicaea than Athanasius. But this close association had more to do with the aftermath of the council than with the event itself.

Three facts are given to support this claim:

First, the fathers at Nicaea had formalized in the church a ranking patriarchal structure, according to which the bishops of Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch would exercise general oversight of the other churches in their respective regions. Thus, when Athanasius was made Bishop of Alexandria in 328, just three years after Nicaea, he suddenly found himself in one of the most prestigious positions in the whole church.

Second, Nicaea had also determined that the church at Alexandria, because of the superior records and resources of astronomy available in that city, would be charged with establishing the proper date of Easter each year, and so informing the rest of the church. This arrangement gave Athanasius an official opportunity to send an annual letter to all the other major ecclesiastical centers, and, until his death in 373, he used these "Paschal Letters" as a means of teaching and admonishing Christians far beyond the borders of Alexandria. As a result, the bishopric of Alexandria became one of the most influential teaching authorities, second only to Rome.

Third, because Nicaea had implicitly granted the Roman emperors an authority over the affairs of the church that they had never had before. the next several decades (even centuries) would see many instances of direct interference with the teaching ministry of the churches, including the office of bishop. As various emperors interfered, Athanasius was forced into exile from Alexandria no fewer than five times.

Athanasius spent those extended periods of banishment chiefly doing two things. First, he traveled extensively to far-off places, where he conferred with church leaders about the Arian heresy and other matters, including imperial interference. These meetings extended Athanasius' reputation as a universal Christian teacher. Second, these periods of exile afforded him ample time to write the lengthy theological treatises that caused him to be ranked, even today, among the greatest exponents of Christian doctrine.

(Source: Christian History & Biography, by Patrick Henry Reardon, an archpriest of the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese, and author, lecturer, podcaster, and senior editor of Touchstone)

Bishop Alexander of Alexandria

Alexander could not have become the bishop of Alexandria at the worst time. Harsh persecutions had taken many lives in Egypt between 303 and 311. Persecution also caused a schism between Bishop Peter of Alexandria and Melitius of nearby Lycopolis. The violence resulted in Peter's death, however, and Alexander stepped into the position of bishop in 313. But the schism raged on.

Just five years later, Alexander began to receive complaints about the teachings of one of his priests, Arius. Mellitus led the grumblers. Alexander attempted to handle the matter in-house, calling Arius before a meeting of local clergy and insisting that he change his message. When Arius refused, Alexander assembled about 100 bishops from Egypt and Libya to denounce the renegade. The council banished Arius, but he did not give up. He enlisted the support of Eusebius of Nicomedia, Eusebius of Caesarea, and many other eastern bishops. Alexander could not keep a lid on the conflict, so Constantine eventually stepped in.

In spite of his gentle and quiet manner, Alexander was unflinching in his theological convictions. He resolutely rejected all attempts, even those led by Constantine, to reinstate Arius. The night before Arius and his supporters planned to force their way into Alexander's church. Alexander reportedly threw himself on the floor of his sacristy, weeping and praying. Arius's death the next morning curtailed the Arian threat to the city, but the Melitians continued to make trouble. Upon Alexander's death in 328, Melidtians resisted Athanasius's election and ultimately elected their own bishop.

(Source: Christian History & Biography, by Elisha Coffman, senior editor, Winter 2005)

Father of Church History

Eusebius of Caesarea was probably the most learned Christian of his time. He was also an ardent admirer of Constantine and his work. For this reason, he has been depicted sometimes as a spineless man who allowed himself to be swayed by the glitter of imperial power. But things are not so simple when you consider his entire career.

Eusebius was born around the year AD 260, most likely in Palestine. He is known as Eusebius "of Caesarea" because he spent most of his life in that city and served as bishop.

A person who left a deep impression on Eusebius was Pamphilus, also of Caesarea. Pamphilus went to that city and worked in the library there, helping the church father Origen build its collection of writings. Pamphilus was joined in this task by Eusebius and others, who spent several years working as a team. Eusebius also traveled widely in the quest for documents about Christian origins.

But their peaceful and scholarly life would eventually come to an end. It was still the time of persecution under Emperor Diocletian. By June of 303, the first martyrdom in many years took place in Caesarea. From then on, the storm grew worse. In 307, Pamphilus was arrested, but Eusebius was not--why this was so isn't clear. One reason might be that he chose to leave the city during this time.

In the midst of such evil times, Eusebius carried on with what would become his most important work, his Church History. This volume, which he later revised, became of great importance to future church historians. Eusebius collected, organized, and published practically all that is now known about many of the people and events in the life of the early church.

The situation began to change in AD 311, however. First came the edict by Galerius that granted tolerance to Christians, and then the Edit of Milan, which put an end to the persecution. Eusebius and other survivors believed all this was happening because God had intervened--similar to the events of Exodus.

Eusebius had been the bishop of Caesarea for a number of years when a new storm broke the peace of the church. This was not persecution by the government, but rather a bitter theological debate that threatened to rend the church asunder: the Arian controversy over the divine nature of Jesus.

For Eusebius, the peace and unity of the church were of prime importance. At first, he seemed to support Arianism at the Council of Nicaea but then took an opposing stance--only to waver again once the council had disbanded. Since he was a famous bishop and scholar, many looked to him for direction, and his confusion did little to conclude the controversy.

Eusebius had met Constantine but was neither a close friend nor a courtier of the emperor. Instead, he spent most of his time in Caesarea and the surrounding area, busy with ecclesiastical matters. But since many of his colleagues admired Eusebius, the emperor cultivated his support. Eusebius was convinced that Constantine had been raised up by God and didn't hesitate to support the emperor. After Constantine's death in AD 337, Eusebius wrote his lines of the highest praise for the ruler who had brought peace to the church in the empire.

His gratitude went far beyond simple words of praise, however. His understanding of what had taken place in Constantine's life left a mark on the bishop's understanding of the history of the Christian church up to his time. Therefore, his actions are not so much those of a flatterer as those of a rather uncritical, but grateful, man. And even in this regard, he was more measured than some of his contemporaries.

The final draft of Eusebius' Church History didn't simply seek to retell the events in the early church. It was an apology that sought to show that Christianity was the ultimate goal of human history, particularly as seen within the context of the Roman Empire.

Similar notions had appeared earlier when Christian writers in the second century declared all truth comes from the same Logos incarnate in Jesus Christ. According to such authors as Justin and Clement of Alexandria, both philosophy and Hebrew scripture were given as a preparation for the gospel.

Also circulating was the idea the empire had been ordained by God as a means to facilitate the spread of the Christian faith. Others, such as Irenaeus, had held that all human history had been a vast process by which God was training humankind for communion with the divine.

What Eusebius then did was to bring together these various ideas, showing them at work in the verifiable facts of the history of both the church and the empire. The history that resulted was no mere collection of data of antiquarian interest, but rather a further demonstration of the truth of Christianity, which is the culmination of human history.

(Source: The Story of Christianity: The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation, by Justo González, revised and updated, 2010)

The Final Act

It took almost 60 years for the church to make Nicaea its standard of faith. For many modern Christians, the Council of Nicaea in AD 325 marks a basic decision of the church about its faith. After that crucial event, all who disagree with its instance that the Son is one being (homoousios) with the Father could only be considered heretics.

But that's not how people saw it then. The idea that Nicaea was a turning point developed gradually over the decades. Modern Christians should accept the church's decision for Nicaea and the Trinitarian faith, but they ought to know the Spirit only slowly led believers to the true reading of Scripture.

There are two reasons Nicaea was not originally regarded as a decisive moment.

First, the idea that creed with fixed wording might be a standard of belief had not yet developed. The council made an ad hoc decision, and it stated its faith in terms that differed from those of Arius. But nobody at Nicaea assumed this wording would stand as the basic Christian confession for centuries to come. Local creeds continued to be used for teaching converts and children until the next century. One of the best examples is the Apostles' Creed.

Second, the controversy between Arius and Alexander was the product of wider tensions in the early fourth-century church. Nicaea was one battle in a much wider war between different ways of interpreting Scriptures about the Father and the Son. This conflict continued for decades. Some books today have also presented the fourth century as the period in which "Jesus became God." The idea that Christians did not previously consider Jesus divine is, however, unfounded nonsense.

New opponents to the creed

Arius played a key role in the events that led up to the Council of Nicaea, but he didn't have a part in the controversies that raged between 325 and 381. Here are the main players in the debate that erupted in the years after Nicaea:

Marcellus of Ancyra: one of the most important leaders of Nicaea itself, but one who had strongly unitarian tendencies.

Athanasius: bishop of Alexandria from 328. In 336 and 339 he was exiled on various charges, including he had been violent towards his opponents. He presented his enemies as "Arians" rather than "Christians."

The Eusebians: a large group of Eastern bishops who included church historian Eusebius of Caesarea and the lesser-known Eusebius of Nicomedia.

Heterophobia

During the 350s, the controversy shifted considerably. This was partly because of Constantius (one of the former emperor's three sons), and partly because new "Heterousian" theologies emerged. Constantius strongly opposed Athanasius, whom he considered dangerous. He supported the Homoians who argued that the Son is "like" (homoios) the Father but a distinct and inferior being. The most radical wing of this movement insisted the Father and Son were unlike in being. This group was the Heterousians, also called Eunomians.

Emperor strikes back

In 359 and 360, Constantius pressured two councils to promulgate the Homoian creed. This was of immense importance. Until then, the Nicene Creed was growing in use in the empire, although not everywhere. Faced with this problem, the emperor and his advisors sought to force provincial councils and individual bishops to agree to one creed.

In the face of this policy, only one creed--the Nicene--could stand as a clear alternative. Between 360 and 380, the policies of Constantius and the rise of Heterousian theologies prompted a variety of groups to coalesce around the Nicene Creed as a standard of faith. This coming together of different groups was made possible in part by the death of Constantius in 361. His sudden death and the antipathy of his successor Julian towards Christianity meant that the Homoian creed never had the chance to gain a firm foothold.

Three in one mystery

This understanding between these previously opposing groups involved a difficult negotiation towards a core faith in which they agreed Nicaea would be a symbol. Two key themes united pro-Nicaea theologians.

First, the pro-Nicenes agreed that God was not divided, and persons of the Godhead were distinct from each other. What mattered was that God was one but also three. This was a mystery. In this context, it seemed much more possible to say the Father and Son were of one "essence" without implying that God was material or that Father and son were "parts" of God.

Second, the pro-Nicenes emphasized that human beings would always fail to comprehend God and that one could only make progress toward knowledge and love of God through discipline and practices that would reshape the imagination.

To Constantinople and beyond

In 381 the rapprochement of the previous two decades resulted, through the help of the pro-Nicene emperor Theodosius, in the Council of Constantinople. This council promulgated a revised version of Nicaea's creed that is still used by Christians today. The council added clauses on the Spirit to insist that "with the Father and the Son He is worshipped and glorified."

Groups of non-Nicene Christians continued to be a real force through the next century, but they became distinct and isolated ecclesial groups. Advocates of Homoian theology gradually came to accept the Nicene faith.

Christians believe that in Christ the Word of God who is eternally one with the Father was at work. They believe that the Spirit who is one with the Father and Son filled the earliest Christian community at Pentecost. Christians should also never forget that the Spirit is the Spirit of truth who dwells in this community, leading it into truth (John 14:17, 26). The story of the fourth century is one of the most important examples of this leading.

(Source: Christian History & Biography by Lewis Ayres, assistant professor of historical theology at Emory University, Winter 2005)

The Christian Codex

Today, there are roughly 100 New Testament papyrus manuscripts in the world. Some were found in the last century, others only a few years ago.

Many others have yet to be published, along with some fragments whose nature is still being debated by scholars.

Until the end of the first century A.D., most writings of classical antiquity were kept as rolls, or scrolls, in libraries such as the great one in Alexandria, Egypt. Both leather and papyrus were used, and scribes usually wrote on one side, arranged in columns of text. You read a scroll by holding it in one hand and rolling it up with the other. They came in different lengths and would be prepared in multiple volumes.

Gradually, however, a new form replaced the rolls derived from the wooden writing tablet that ancient people used for making notes. When more space was needed, scribes merely stacked boards together by drilling holes along one edge and passing a cord through them, creating a notebook. Over time, deluxe models were made of ivory instead of wood. The Roman name for the tablet notebook was codex.

Julius Caesar may have been the first Roman to reduce scrolls to bound pages in this form, the prototype of today's book. Sometime later, the Romans devised a lighter notebook, first using papyrus and then parchment. They would lay two or more sheets on top of each other and then pass a cord through to hold them together. It was only a short step from binding up a few sheets to joining many of them to hold longer writings, such as accounts, notes, and letters.

Archaeological excavations have shown that early Christians preferred the codex for making copies of the Scriptures because this form was easier to carry, read, and store than a scroll. However, they also adopted the codex to distinguish their writings from sacred Jewish books and from pagan literature--both of which were written on rolls of papyrus or parchment. More importantly, though, the codex permitted the copying of much longer texts, such as Luke's gospel, to be contained within a single volume and read more easily.

There is no known evidence, thus far, to prove that Luke actually possessed a codex of his writings. But the possibility still exists. Biblical scholars C.H. Roberts and T.C. Skeat, co-authors of The Birth of the Codex, have argued that Christian use of the codex was so widespread in the second century, "that its introduction must date well before A.D. 100." Skeat also believed that Christians developed "a primitive form of the codex, whose use spread quickly from Antioch."

The earliest preserved examples of the Christian codex date to the second century. There are 11 papyrus codices of this period--six containing parts of the Septuagint, the Greek version of the Old Testament, and five including portions of the New Testament.

The use of the codex by Christian writers expanded greatly as time went on. Most of these manuscripts were made of papyrus, but many were also of parchment, such as the 50 Bibles that Constantine ordered Eusebius to produce.

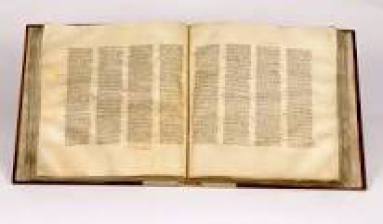

There are many Christian codices, and two of the oldest and most well-known that we have today were written in the fourth century: the Vaticanus and the Sinaiticus.

The Vaticanus includes virtually all of the Septuagint and most of the New Testament. Portions of the codex were gathered by various scholars and contain numerous errors. It was written in Greek on expensive vellum, a fine parchment made from calfskins, with the uncial (capital letters) text of each page arranged in three columns. This codex was found in the Vatican Library in the late 15th century and remains there today.

The Sinaiticus contains part of the Old Testament and all of the New Testament on fine vellum, arranged in four columns of uncial text. This codex was found by a German biblical scholar at St. Catherine's Monastery on the slopes of Mount Sinai in 1844. It is on display at the British Library and is available for viewing online.

Scholars have debated whether Constantine wanted complete Bibles or only sets of the four Gospels. The late T.C. Skeat, who was a librarian at the British Museum, suggested that the Vaticanus and Sinaiticus, both now faded and worn, might have been among the 50 Bibles prepared by Eusebius' scribes at Caesarea.

We may never know the true history of these two magnificent codices. Yet each was written by scribes using the existing canon of scripture at that time and perhaps even a rare manuscript such as the fictional Nicaea Codex of this trilogy.

Jesus and His disciples quoted from what we call the Old Testament during their ministries. Soon, though, letters of the apostles such as Paul and Peter were brought together, followed by the four Gospels and other teachings. And, by the middle of the second century, there was an early canon of these writings that included most books of our modern New Testament.

What Early Christians Were Like

It would be a mistake to romanticize the early church as an age of purity to which we should seek to return. The churches always had their problems and internal struggles. Nevertheless, the early churches as a whole did represent something different in their world. It attracted both devoted followers and brutal persecutors. To see what these early believers were like, let's go to the sources and hear what they were bold to proclaim about themselves.

First Apology of Justin Martyr (AD 150)

First, an early philosopher, Justin Martyr, wrote to the Roman emperor, Antonius Pius around AD 150 to defend the Christians. The "apology" was not saying "sorry" but was a defense of a viewpoint. In the excerpt below we see how the believers were eager to invite the most intense scrutiny of their lives. At the same time note how Justin Martyr reminds the most powerful man in that world that he may not really be as much in charge as he thinks.

"Since you are called pious and philosophers, guardians of justice and lovers of learning, pay attention and listen to my address. If you are indeed followers of learning, it will be clear. We have not come to flatter you by this writing nor please you by our address, but to beg that you pass judgment after an accurate and searching investigation. . . . As for us, no evil can be done to us unless we are convicted as evildoers or proved to be wicked men. You can kill us. But you cannot hurt us.

"To avoid anyone thinking that this is an unreasonable and reckless declaration, we demand that the charges against the Christians be investigated. If these are substantiated, we should be justly punished. But if no one can convict us of anything, true reason forbids you to wrong blameless men because of evil rumors. If you did so, you would be harming yourselves in governing affairs by emotions rather than by intelligence . . . . It is our task, therefore, to provide to all an opportunity of inspecting our life and teachings . . . . It is your business, when you hear us, to be good judges, as reason demands. If, when you have learned the truth, you do not do what is just, you will be without excuse before God."

Epistle to Diognetes (AD 130)

Here is a gem we are most fortunate to have as only one copy survived the centuries. We do not know who wrote it. It came from the second century. It was, as the New Testament, originally written in Greek. In this brief excerpt, we have preserved a magnificent description of Christian living in what was expected in the early church community.

"For the Christians are distinguished from other men neither by country, nor language, nor the customs which they observe. For they neither inhabit cities of their own, nor employ a peculiar form of speech, nor lead a life which is marked out by any singularity. The course of conduct which they follow has not been devised by any speculation or deliberation of inquisitive men; nor do they, like some, proclaim themselves the advocates of any merely human doctrines. But, inhabiting Greek as well as barbarian cities, according to as a lot of each of them has determined and following the customs of the natives in respect to clothing, food, and the rest of their ordinary conduct, they display to us their wonderful and confessedly striking method of life.

"They dwell in their own countries, but simply as sojourners. As citizens, they share in all things with others and yet endure all things as if foreigners. Every foreign land is to them as their native country and every land of their birth as a land of strangers. They marry, as do all others; they beget children, but they do not destroy their offspring. They have a common table, but not a common bed. They are in the flesh, but they do not live after the flesh. They pass their days on earth, but they are citizens of heaven. They obey the prescribed laws, and at the same time surpass the laws in their lives.

"They love all men and are persecuted by all. They are unknown and condemned; they are put to death and restored to life. They are poor yet make many rich; they are in lack of all things and yet abound in all; they are dishonored and yet in their very dishonor are glorified. They are evil spoken of and yet are justified; they are reviled and bless; they are insulted and repay the insult with honor; they do good yet are punished as evildoers. When punished, they rejoice as if quickened into life; they are assailed by the Jews as foreigners and are persecuted by the Greeks, yet those who hate them are unable to assign any reason for their hatred. To sum it all up in one word -- what the soul is to the body, that are Christians in the world."

Apology of Tertullian (AD 197)

One of the most lively early church scholars was Tertullian, the North African who lived from around AD 160-225. He commended the Christian faith to the pagan world. In this excerpt, we get priceless insight into the practices of early Christian worship, discipline, leadership selection, and financial giving. But most significantly, Tertullian preserves the amazing pagan observation of the Christians: "See how they love one another."

"We are a body knit together as such by a common religious profession, by unity of discipline, and by the bond of a common hope. We meet together as an assembly and congregation, that, offering up a prayer to God as with united force, we may wrestle with Him in our supplications. This strong exertion God delights in. We pray, too, for the emperors, for their ministers and for all in authority, for the welfare of the world, for the prevalence of peace, for the delay of the final consummation. We assemble to read our sacred writings . . . and with the sacred words we nourish our faith, we animate our hope, we make our confidence more steadfast; and no less by inculcations of God’s precepts we confirm good habits. In the same place also exhortations are made, rebukes and sacred censures are administered.

"For with a great gravity is the work of judging carried on among us, as befits those who feel assured that they are in the sight of God; and you have the most notable example of judgment to come when anyone has sinned so grievously as to require his severance from us in prayer, in the congregation, and in all sacred intercourse. The tried men of our elders preside over us, obtaining that honor not by purchase but by established character. There is no buying and selling of any sort in the things of God. Though we have our treasure chest, it is not made up of purchase money, as of a religion that has its price.

"On a monthly day, if he likes, each puts in a small donation; but only if it be his pleasure, and only if he be able: for there is no compulsion; all is voluntary. These gifts are . . . not spent on feasts, and drinking-bouts, and eating-houses, but to support and bury poor people, to supply the wants of boys and girls destitute of means and parents, and of old persons confined now to the house; such, too, as have suffered shipwreck; and if there happen to be any in the mines or banished to the islands or shut up in the prisons, for nothing but their fidelity to the cause of God's Church, they become the nurslings of their confession. But it is mainly the deeds of a love so noble that lead many to put a brand upon us. See, they say, how they love one another, for they themselves are animated by mutual hatred. See, they say about us, how they are ready even to die for one another, for they themselves would sooner kill."

Pliny writes to Trajan about the "Christian Problem"

Pliny, the Roman governor in Bithynia, in present-day Turkey, had a problem. What was he to do with the Christians who were spreading rapidly? He wrote to his emperor Trajan in Rome, seeking advice. He describes the Christian problem and shows how some under pressure were willing to renounce their faith and others were not. He then gives valuable descriptions of the Christian life, practice, and worship at that time.

"An anonymous document was published containing the names of many persons. Those who denied that they were or had been Christians, when they invoked the words dictated by me, offered prayer with incense and wine to your image, which I had ordered to be brought for this purpose together with statues of the gods, and moreover cursed Christ -- none of which those who are really Christians, it is said, can be forced to do -- these I thought should be discharged. Others named by the informer declared that they were Christians, but then denied it, asserting that they had been but had ceased to be, some three years before, others many years, some as much as twenty-five years.

"They all worshipped your image and the statues of the gods and cursed Christ. They asserted, however, that the sum and substance of their fault or error had been that they were accustomed to meet on a fixed day before dawn and sing responsively a hymn to Christ as a god, and to bind themselves by oath, not to some crime, but not to commit, fraud, theft, or adultery, not falsify their trust, nor to refuse to return a trust when called upon to do so. When this was over, it was their custom to depart and to assemble again to partake of food -- but ordinary and innocent food. Even this, they affirmed, they had ceased to do after my edict by which, in accordance with your instructions, I had forbidden political associations. Accordingly, I judged it all the more necessary to find out what the truth was by torturing two female slaves who were called deaconesses. But I discovered nothing else but depraved, excessive superstition."

(Source: Christianity.com)

How Early Christians Worshipped

In his First Apology (155 A.D.), the second-century Christian apologist Justin Martyr wrote a fascinating account of Christian worship and faith. Here is an excerpt from this classic book:

How we dedicated ourselves to God when we were made new through Christ I will explain, since it might seem to be unfair if I left this out from my exposition.

Those who are persuaded and believe that the things we teach and say are true, and promise that they can live accordingly, are instructed to pray and beseech God with fasting for the remission of their past sins, while we pray and fast along with them.

Then they are brought by us where there is water, and are reborn by the same manner of rebirth by which we ourselves were reborn; for they are then washed in the water in the name of God the Father and Master of all, and of our Saviour Jesus Christ, and of the Holy Spirit. For Christ said, "Unless you are born again, you will not enter into the Kingdom of heaven."

Now it is clear to all that those who have once come into being cannot enter the wombs of those who bore them. But as I quoted before, it was said through the prophet Isaiah how those who have sinned and repent shall escape from their sins.

He [Isaiah] said this: "Wash yourselves, be clean, take away wickedness from your souls, learn to do good, give judgment for the orphan and defend the cause of the widow, and come let us reason together, says the Lord. And though your sins be as scarlet, I will make them as white as wool, and though they be as crimson, I will make them as white as snow."

After thus washing the one who has been convinced and signified his assent, [we] lead him to those who are called brethren, where they are assembled. They then earnestly offer common prayers for themselves and the one who has been illuminated and all others . . . that we may be made worthy, having learned the truth, to be found indeed good citizens and keepers of what is commanded, so that we may be saved with eternal salvation.

On finishing the prayers we greet each other with a kiss. Then bread and a cup of water and mixed wine are brought to the president of the brethren and he, taking them, sends up praise and glory to the Father of the universe through the name of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and offers than thanksgiving at some length that we have been deemed worthy to receive these things form him.

When he has finished the prayers and the thanksgiving, the whole congregation present assents, saying. "Amen" . . . When the president has given thanks and the whole congregation has assented, those who we call deacons give each of those present a portion of the consecrated bread and wine and water, and they take it to the absent.

This food we call Eucharist, of which no one is allowed to partake except one who believes that the things we teach are true and has received the washing for forgiveness of sins and rebirth, and who lives as Christ handed down to us. . . .

Those who prosper, and who so wish, contribute each one as much as he chooses to. What is collected is deposited with the president, and he takes care of orphans and widows, and those who are in want on account of sickness or any other cause, and those who are in bonds, and the strangers who are sojourners among [us], and, briefly, he is the protector of all those in need.

We all hold this common gathering on Sunday since it is the first day, on which God transforming darkness

and matter made the universe and Jesus Christ our Saviour rose from the dead on the same day.

(Source: ChristianityToday.com/history, August 2008)

Liturgy of the Early Church

Early Christians shared with Jews the conviction that 'religion' included an interpretation of life, and that it was not limited to actions and ceremonies. They also shared the idea that God had given certain covenant signs of his grace.

Christians in the early church thought circumcision was limited to Judaism and not binding on Gentiles. They kept the Jewish sacraments of baptism when welcoming new converts, and the bread and wine of Passover when observing communion in the Last Supper.

As early as Paul's time it was customary for Christians to worship on Sunday in commemoration of the Lord's resurrection. This weekly association of 'the Lord's day' led to moving the annual celebration of Easter from the date of the Jewish Passover on the fourteenth day of Nisan to the Sunday following it.

It was not long that Christians adopted other Jewish observances, such as Pentecost. By the fourth century, the church calendar included Ascension Day and the nativity of Christ (Christmas)--celebrated on December 25 in the western empire and on January 6 in the east.

Like the Jews, the early Christians kept certain days for fasting. Jews fasted on Mondays and Thursdays, while Christians did so on Wednesdays and Fridays. By the beginning of the fourth century, the fast before Easter lasted seven days in the east but forty days in the west. This six-week time of self-denial before Easter Sunday became Lent, initiated by Athanasius after being exiled to the west.

The days of Holy Week evolved, first with the observance of Maundy Thursday, then (by the sixth century) Palm Sunday. The custom of not holding a celebration of the Eucharist on Good Friday is found as early as the year 416.

What form did church services take before Constantine and the Nicene council? There are only fragments of evidence in casual allusions or in illustrations.

For instance, Tertullian describes the rite of Baptism in North Africa in AD 200. After a time of fasting, the candidate renounced the devil and his works and declared his or her faith in God. The bishop or presbyter then dipped the person in the water after answering three questions about the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. He then anointed the person with oil and laid hands on the new believer with prayer for the gift of the Holy Spirit. The person also received milk and honey as tokens of his entry into the Promised Land.

In principle, it was more desirable to baptize people in a river or lake before the end of the first century A.D. But in practice, it had become customary to conduct the sacrament simply by pouring water on the candidate's head three times.

The symbolism of partial immersion in running water, however, was preserved by constructing special baptisteries in house churches or, after the fourth century, adjacent to the main building. Candidates would descend a few steps and stand in water. The ceremony was intensely solemn and included exorcisms.

Then as now, baptism is meant to symbolize dying to sin and rising again to newness of life with Christ; therefore it was associated with Easter and Pentecost.

(Source: The Early Church by Henry Chadwick, revised edition, 1993)

The earliest second-century texts agree that regular Sunday worship by Christians was primarily a 'thanksgiving', eucharistic--a term that gradually replaced the words 'breaking of bread.'

The local church bishop admitted only baptized believers to the sacred meal. Justin Martyr describes the Roman Eucharist in the year 150 in a passage that reassures pagan readers that Christian rites are not black magic.

In the Eucharist sacrament, the bishop first read from 'the memoirs of the apostles and from the Old Testament prophets. He then preached a sermon, after which everyone stood for a solemn prayer ending in the kiss of peace. Next, deacons brought the bread and wine mixed with water to the bishop, who offered a prayer of thanks to the Father through the Son and Holy Spirit--concluding with everyone saying Amen.

Then came the Communion, at which each person ate the bread and drank the wine distributed by deacons. They received it, not as a common food for satisfying hunger and thirst, but as the flesh and blood of Christ.

The sacred meal closed with a prayer of thanksgiving. There were no prescribed words. The presiding bishop was free in his wording, as long as it followed an expected pattern.

Perhaps an early model for this prayer may have been included in the Didache, a first-century Christian treatise also called the Teaching of the Twelve Apostles.

After the Didache, the earliest extant forms of prayer--other than the briefest fragments--are preserved in the Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus, the most important third-century theologian of the Christian church in Rome. The text of this work does not survive exactly as he wrote it but is reconstructed by scholars from later compilations and from church orders.

As congregations grew in size during the fourth century, the liturgy grew in length as bishops often expanded older prayers by inserting biblical quotations. They also wore ornate robes during elaborate ceremonies, especially in Eastern Greek churches. At the same time, the pressure of so many people joining the church, and perhaps the struggle against Arianism, led to an instance of an atmosphere of 'holy awe' and on the 'transcendent wonder' of the Eucharist.

In preserved copies of lectures by Cyril of Jerusalem, about 350, the distinguished theologian speaks of elaborate ceremonies and of intense awe appropriate for the sacrament. Cyril provides evidence that celebrants washed their hands in a symbolic manner before taking the bread and wine.

He also gives detailed instructions to prevent any irreverent dropping of the communion elements. Participants receive the bread in hollowed palms, the left hand supporting the right. Above all, Cyril mentions the solemn innovation of the Spirit by which, in faith, the bread and wine become Christ's body and blood, and speaks of the 'fearful' presence upon the Lord's Table.

In addition to observing the Eucharist on Sundays, believers celebrated on the days of saints and martyrs as well as offered private prayers daily. Hippolytus, in the Apostolic Tradition, directed that Christians should pray seven times a day--on rising, at the lighting of the evening lamp, at bedtime, at midnight, and also, if at home, at the third, sixth, and ninth hours of the day (relating to Christ's Passion).

(Source: The Early Church by Henry Chadwick, revised edition, 1993)

Twice in the letters of Paul, we find allusions to singing in worship in the early church, as was apparently the custom in Jewish synagogues.

Philo of Alexandria describes the musical life of a nearby ascetic community. Christians wrote hymns in different meters and tunes, with notations to show the proper rhythm in concert with sacred music. Choirs of men and women chanted in harmony or in response to words of liturgy.

A few Greek hymns survive from the time before Constantine. One is a rollicking second-century hymn of joy, which may have been sung at the Paschal vigil. It takes place in the form of a wedding hymn of exultation that the lost bridegroom has been found. It runs:

Praise the Father, you holy ones.

Sing to the Mother, you virgins.

We praise. We the holy ones extol them.

Be exalted, brides and bridegrooms.

For you have found your bridegroom, Christ.

Drink your wine, brides, and bridegrooms.

A second example is on a third-century papyrus from Egypt, a well-preserved hymn where all creation joins the church in praising the Trinity:

While we hymn Father, Son and Holy Spirit, let all creation sing Amen.

Praise, power to the sole giver of all good things. Amen, Amen.

Another is an evening hymn in general use in the time of Basil the Great and still forming part of Greek Vespers, sung at the lighting of the evening lamp:

Hail, gladdening Light, of his pure glory poured

Who is the immortal Father, heavenly, blest,

Holiest of Holies, Jesus Christ our Lord.

Now we are come to the sun's hour of rest,

The lights of evening round us shine,

We hymn the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit divine.

Worthiest art thou at all times to be sung

With undefiled tongue,

Son of our God, giver of life, alone:

Therefore in all the world thy glories, Lord, they own.

As choirs grew in size, it became possible to have two groups of singers chanting alternately. This practice came into use during the second half of the fourth century and spread from Mesopotamia and Syria.

Music in worship was not approved by everyone. A few strong-minded puritans wanted to ban it completely and found a measure of support from those who felt that chanting obscured the meaning of the words.

But most Christians enjoyed the music. In his Confessions, Augustine writes how moving he found the psalm chants in use in Milan. He felt the words were invested with far greater power when they were associated with the music of haunting beauty. Augustine observes there is no emotion of the human spirit that music is incapable of expressing.

(Source: The Early Church by Henry Chadwick, revised edition, 1993)

When Christians retained the Old Testament for their own use, they didn’t completely settle the question of just which books this included. To this day, Christians still differ over the inclusion or rejection of the so-called Apocrypha in the Old Testament.

Apocrypha stands for twelve or fifteen books, depending on how you group them, that Roman Catholics accept as canonical and most Protestants reject.

The question is complicated. The debate centers on the fact that Jews in Palestine had a canon matching the thirty-nine books of the Protestant Old Testament. Jesus referred to this list when he spoke of the Law of Moses, the prophets, and the Psalms (Luke 24:44). The evidence seems to indicate that neither Jesus nor his apostles ever quoted from the Apocrypha as Scripture.

Beyond Palestine, however, Jews were more inclined to consider as Scripture those writings not included in this list. The Greek translation of the Old Testament, the Septuagint, was influential in making known certain books of the Apocrypha.

Early Christians also differed, then, over the question of the Apocrypha. Believers in the eastern portion of the Roman Empire tended to agree with Jews in that area. In the West, however, Christians under the influence of Augustine, the bishop of Hippo, usually received the Apocrypha as part of the canon.

From the beginning, however, Christians had more than the Old Testament as their rule for faith. While Jesus was on earth, they had the Word made flesh, and after His ascension, they had the living leadership of the apostles.

During the days of the apostles, congregations often read letters from the Lord’s companions. Some of these letters were intended to be read aloud in public worship, probably alongside portions of the Old Testament or with a sermon.

Churches also relied on accounts about Jesus’ life. Although the first Gospels were not written before AD 60 or 70, their contents were partly available in written form before this time. Luke tells us that many people had undertaken such accounts.

How did the twenty-seven books we know as the New Testament come to be set apart as Scripture?

First, the books that are included in the Bible possess a unique, authentic quality of their own as the Word of God. They have exercised an unparalleled power in people’s lives down through the ages.

As a young man, Justin Martyr searched for truth in a variety of schools of philosophy but none of them satisfied him. One day, while meditating alone by the seashore—perhaps in Ephesus—he met an old man. As they talked, the stranger exposed the weakness of Justin’s thinking and urged him to turn to the Jewish prophets. By reading Scripture, Justin became a Christian. Scores of other men and women in the early days of the church had a similar experience.

One of the primary reasons, then, behind the adoption of the New Testament books as Scripture was this self-authenticating quality.

Second, certain Christian books were added to Scripture because they were used in worship. Even in the New Testament itself, there are signs that the reading of Scripture was very much a part of congregational life. The apostle Paul urged the Colossians: "After this letter has been read to you, see that it is also read in the church of the Laodiceans and that you, in turn, read the letter from Laodicea" (Col. 4:16).

Justin Martyr, writing in the middle of the second century, gives us the first description of a Christian church service:

"On the day called the Day of the Sun all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs and prays."

The mere act of reading a book in Christian worship did not assure the writing an eventual place in the canon. We know, for example, that Clement, the bishop of Rome, wrote a letter to the church at Corinth about AD 96, and eighty years later, it was still the custom in Corinth to read his letter in public worship. Yet his letter was never added to the canon.

Third, and perhaps the main reason behind a Christian book's acceptance into the New Testament, was its ties with an apostle. This was the test of a book's validity: Was it written by an apostle, or at least by a man who had direct contact with the circle of apostles?

In the early church, the apostles held a place that other men simply could not fill. Believers always regarded them as men who had a unique relationship with the Lord. Did not Jesus say: "He who receives you receives me" (Matt. 10:40)? Any gospel or letter, therefore, which could make a strong claim to apostolic authorship, stood a good chance of acceptance as Scripture.

(Source: Church History in Plain Language by Bruce Shelley, 1995)