First to Fourth Century

Christianity in the First Century

The 1st century is focused on the formative years of the Christian faith. The earliest followers of Jesus are primarily Jews, which historians refer to as the Jewish community. The apostles left Jerusalem, following the Great Commission of Jesus to spread His teachings to "all nations".

Peter, Paul, and James the Just were the most influential early leaders, though Paul's influence on Christian theology is said to be more significant than any other New Testament authors. The split of early Christianity from Judaism was gradual, as Christianity spread over the Roman Empire and Europe.

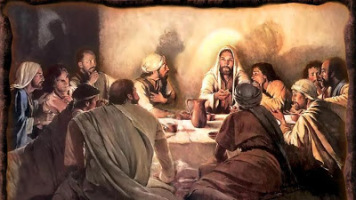

The ministry of Jesus, according to the Gospels, began with his baptism by John the Baptist in the Jordan. Jesus preached for a period of three years in the early 1st century AD. He used parables, metaphors, allegory, sayings, proverbs, and sermons such as the Sermon on the Mount. His ministry was ended by crucifixion at the hands of Roman authorities at the demand of the Jews in Jerusalem.

Three days after his death, Jesus rose bodily from the dead. His resurrection is the basis and impetus of the Christian faith. His followers document in the New Testament of the Bible a number of resurrection appearances, including more than 500 witnesses at one time. Jesus appeared to the disciples in Galilee and Jerusalem and was on the earth for 40 days before his ascension to heaven and returning to God the Father. Jesus promised to return to earth to completely fulfill the Messianic prophecy, including the resurrection of the dead, the last judgment, and the establishment of the eternal Kingdom of God.

The main sources of information about Jesus' life and teachings are the four canonical gospels of the New Testament, the Acts of the Apostles, and the writings of Paul. Christianity is based on the central point that Jesus, the Anointed One, died and rose from death as God's Son and only sacrifice for human sins.

Christianity in the Second Century

The 2nd century was mainly the time of the Apostolic Fathers who were the students of the apostles of Jesus, though there is some overlap as John the Apostle may have survived into the 2nd century and Clement of Rome is said to have died at the end of the 1st.

While the Christian church was centered in Jerusalem in the 1st century, it became decentralized in the 2nd. The 2nd century was also when several people were later declared to be major heretics, such as Marcion, Valentinus, and Montanus.

Although the use of the term "Christian" is attested in the book of Acts from the middle of the 1st century, the earliest recorded use of the term Christian (Greek: Χριστιανισμός) is by Ignatius of Antioch about AD 107, who is also associated with modification of the sabbath, promotion of the bishop, and critique of the Judaizers.

At first, Christians continued to worship and pray alongside Jewish believers, but within twenty years of Jesus' death, the Lord's Day (Sunday) was being regarded as the primary day of meeting and worship among some Christian sects in the city of Rome.

Growing tensions soon led to a starker separation that was virtually complete by the time Christians refused to join in the Bar Khokba Jewish revolt of AD 132, however some groups of Christians retained more elements of Jewish practice. Only Marcion proposed rejection of all Jewish practice, but he was excommunicated in Rome in 144 and declared heretical by the growing proto-Orthodoxy.

Christian communities came to adopt some Jewish practices while rejecting others. Historians debate whether the Roman government distinguished between Christians and Jews prior to Emperor Nerva's modification of the Fiscus Judaicus in 96. From then on, practicing Jews paid the tax, and Christians did not.

Christianity also differed from other Roman religions in that it set out its beliefs in a clearly defined way, though the process of orthodoxy (right belief) was not underway until the period of the first seven Ecumenical Councils. Most early Christians did not own a copy of the works that later became the Christian bible or other church works accepted by some but not canonized, such as the writings of the Apostolic Fathers or other works today called New Testament Apocrypha.

Similar to Judaism, much of the original church liturgical services functioned as a means of learning these Scriptures, which initially centered around the Septuagint and the Targums.

A final uniformity of liturgical services may have become solidified after the church established a Biblical canon, possibly based on the Apostolic Constitutions and Clementine literature. Clement wrote about the order with which Jesus commanded the affairs of the Church be conducted. The liturgies are "to be celebrated, and not carelessly nor in disorder", but he did not specify what the actual liturgies were, though possible Clementine liturgies have been proposed.

Christianity in the Third Century

The 3rd century was largely the time of the Ante-Nicene Fathers who wrote after the Apostolic Fathers of the 1st and 2nd centuries, but before the First Council of Nicene in 325.

Those who wrote in Greek are called the Greek (Church) Fathers. These included Clement of Alexandria, Origen of Alexandria, and Hippolytus of Rome.

Clement (Titus Flavius Clemens) was the first member of the Church of Alexandria to be more than a name, and one of its most distinguished teachers. He united Greek philosophical traditions with Christian doctrine and valued gnosis that with communion for all people could be held by common Christians. He developed Christian Platonism. Like Origen, he arose from the Catechetical School of Alexandria and was well versed in pagan literature.

Origen was an early Christian scholar and theologian. According to tradition, he was an Egyptian who taught in Alexandria, reviving the Catechetical School where Clement had taught. The patriarch of Alexandria at first supported Origen but later expelled him for being ordained without the patriarch's permission. He relocated to Caesarea Maritima and, with his knowledge of Hebrew, produced a corrected Septuagint. He also wrote commentaries on all the books of the Bible. He died in Caesarea after being tortured during a persecution.

Hippolytus was one of the most prolific writers of early Christianity. He was born during the second half of the 2nd century, probably in Rome. He was a disciple of Irenaeus, who was said to be a disciple of Polycarp. He came into conflict with the Popes of his time and for a while headed a separate group. For that reason, he is sometimes considered the first Antipope. However, he died in 235 or 236 reconciled to the Roman church and as a martyr.

Those fathers who wrote in Latin are called the Latin (Church) Fathers. These included Tertullian and Cyprian.

Tertullian, who was converted to Christianity before AD197, was a prolific writer of apologetic, theological, controversial, and ascetic works. He was the son of a Roman centurion. He denounced Christian doctrines he considered heretical, but it has been claimed that later in life he converted to Montanism, a sect that appealed to his rigorism. He wrote three books in Greek and was the first great writer of Latin Christianity, thus sometimes known as the "Father of the Latin Church".

Cyprian was the bishop of Carthage and an important early Christian writer. He was probably born at the beginning of the 3rd century in North Africa, where he received an excellent classical education. After converting to Christianity, he became a bishop in 249 and eventually died a martyr at Carthage.

Christianity in the Fourth Century

The 4th century was dominated in its early stage by Constantine and the First Council of Nicaea. This was the beginning of the first seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787), and in its late-stage by the Edict of Thessalonica of 380, making Nicene Christianity the state church of the Empire.

With Christianity the dominant faith in some urban centers, Christians accounted for approximately 10 percent of the Roman population by AD 300, according to some estimates. Roman Emperor Diocletian launched the bloodiest campaign against Christians that the empire had witnessed.

The persecution ended in 311 with the death of Diocletian. The persecution ultimately had not turned the tide on the growth of the religion. Christians had already organized to the point of establishing hierarchies of bishops. In 301 the Kingdom of Armenia became the first nation to adopt Christianity. The Romans followed suit in 380.

Christian sources record that Constantine experienced a dramatic event in 312 at the Battle of Milvian Bridge, after which he claimed the title of emperor in the West. According to these sources, Constantine looked up to the sun before the battle and saw a cross of light above it, and with it, the Greek words "ΕΝ ΤΟΥΤΩ ΝΙΚΑ" ("by this, conquer!", often rendered in the Latin "in hoc signo vinces"), Constantine commanded his troops to adorn their shields with a Christian symbol (the Chi-Ro), and thereafter they were victorious.

How much of the Christian religion Constantine adopted at this point is difficult to discern; most influential people in the empire, especially high military officials, were still pagan, and Constantine's rule exhibited at least a willingness to appease these factions.

The accession of Constantine was a turning point for the Christian church. After his victory, Constantine supported the church financially, built various basilicas, granted privileges to clergy, promoted Christians to high-ranking offices, and returned property confiscated during the reign of Diocletian. In 313 Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, reaffirming the tolerance of Christians and returning previously confiscated property to the churches.